Hunter S. Thompson, Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail ’72, 1973

In his reporting, Thompson does not seem much interested in Wallace. The Confederate Flag-beating demagogue is less a man than a force of nature—an angry hurricane the casts the struggle between Muskie, Humphrey, Kennedy, and McGovern in sharper relief. But when he does turn to Wallace, there is wisdom there. First vignettes by Thompson; below the jump, Timothy Crouse.

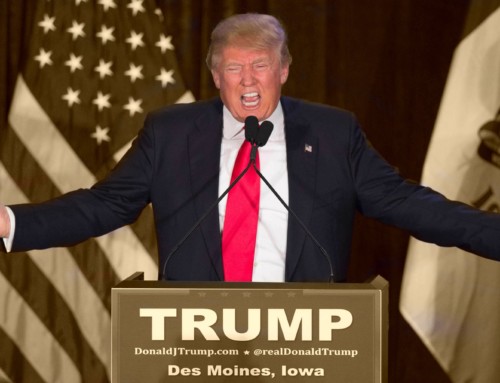

The main problem in any democracy is that crowd-pleasers are generally brainless swine who can go out on a stage & whup their supporters into an orgiastic frenzy—then go back to the office & sell every one of the poor bastards down the tube for a nickel apiece. Probably the rarest form of life in American politics is the man who can turn on a crowd & still keep his head straight—assuming it was straight in the first place…Maybe the whole secret of turning a crowd on is getting turned on yourself by the crowd.

The only candidate running for the presidency today who seems to understand this is George Wallace…

…

The root of the Wallace magic was a cynical, showbiz instinct for knowing exactly which issues would whip a hall full of beer-drinking factory workers into a frenzy—and then doing exactly that, by howling down from the podium that he had an instant, overnight cure for all their worst afflictions: Taxes? Nigras? Army worms killing the turnip crop? Whatever it was, Wallace assured his supporters that the solution was actually real simple, and that the only reason they had any hassle with the government at all was because those greedy bloodsuckers in Washington didn’t want the problems solved, so they wouldn’t be put out of work.

The ugly truth is that Wallace had never even bothered to understand the problems—much less come up with any honest solutions—but “the Fighting Little Judge” has never lost much sleep from guilt feelings about his personal credibility gap. Southern politicians are not made that way. Successful con men are treated with considerable respect in the South. A good slice of the settler population of that region were men who’d been given a choice between being shipped off to the New World in leg-irons and spending the rest of their lives in English prisons. The Crown saw no point in feeding them year after year, and they were far too dangerous to be turned loose on the streets of London—so, rather than overload the public hanging schedule, the King’s Minister of Gaol decided to put this scum to work on the other side of the Atlantic, in The Colonies, where cheap labor was much in demand.

…

There were some Wallace supporters, though, who talked like men of peace, and it was easy to feel sympathetic with them. A short, grey-haired county chairman for Wallace in Florida softly asked me why the media had it in for Wallace. I answered that, first of all, it was because Wallace was for segregation.

“You’re thinking of the old George Wallace, the man in the schoolhouse door,” he said. “He’s for integration now, ’cause it’s the law of the land, ain’t it? He just wants those Northern cities to integrate too.” There is no one harder to argue with than a Wallacite who happens to be a Southern gentleman. They’ll make you feel hypocritical every time, without one nasty word.

…

Off in a corner three old Wallace workers were having a reunion—a middle-aged rake with a pencil moustache who was “in construction”; a man in glasses and a styrofoam Wallace “straw” hat who was an automobile dealer; and a burly gas-station attendant. “Boys, we been together since May 1, 1964—that’s when George Wallace came to the Lord Baltimore Hotel,” said the man in construction. “Madeleine Murray’s son climbed up a fence and tried to take our flag away from us, remember?” “And remember, that Commie from New York wrapped himself in a flag and gave you a hard time?” the auto dealer reminisced. “We might get our country back,” said the construction man, stirred. “I feel like I lost it. I feel like I been lost in it all this time.”

…

“One thing puzzling the press is why there weren’t more Wallace stickers on cars,” the auto dealer told me. “It’s fear. Fear of retaliation from blacks. Of getting bricks thrown at your car.” “You didn’t have any problems down in that black section did you?” asked the construction man. “A few. Just a few,” said the auto dealer. “I think it’s just a small group of black revolutionaries cause the trouble,” the construction man said. Everyone in the room was drunk on victory and quite sure George Wallace was going to win the nomination. Every so often they would cheerfully scoff at a TV commentator who attributed the Wallace victory to a “sympathy vote.”

“A sympathy vote? Definitely not. We never had any doubts he was gonna run away with it in Maryland.”

Leave A Comment