It was the image of a 7-year-old trauma victim, still strapped in his airplane seat after a 30,000 foot fall, which made me quit my work for the night and go outside to gulp breaths of cold, crisp air. I hadn’t gone looking for the picture — I was doing research on the MH17 crash site — but it was one of the top results, and I habitually zoomed in for a better look. You could still make out the look of terror before explosive decompression had robbed him of his consciousness, hopefully the whole way down.

A few years ago, as talking heads fretted about the increasing photorealism of videogame violence, very few people were thinking ahead to how the web might abet the spread photos and videos of real violence. Yet here we are. In the mid-2000s, raw war footage and snuff films lived only in the dark corners of the internet: carefully guarded torrents and unlisted websites, frequented by a tiny minority of very sick people. Now, at the start of 2016, there’s at most two degrees of separation — a hashtag and a video link — between a funny-but-dumb BuzzFeed article and a choreographed ISIS execution. The worlds are gradually converging.

What happens to people who live in this world of digital murder and atrocity, even if they’re ensconced in a cubicle on the other side of the world? The only report I’ve found on the subject, “Making Secondary Trauma a Primary Issue: A Study of Eyewitness Media and Vicarious Trauma on the Digital Frontline,” makes a compelling case that social media analysts charged with monitoring “distressing” content for extended periods may come away with PTSD. 40 percent of its respondents report “high or very high” adverse affects on their personal lives. Because the death and suffering remain a few smartphone taps away, it’s difficult to compartmentalize this work. It’s always with you.

The report is a survey, not a psychological study. But it jives with the feedback of many “open-source intelligence analysts” I’ve talked to and read about, who consistently make reference to the mentally draining nature of their work, particularly when it comes to images of children. Although I’m exposed to only a fraction of the content that they are, I think it does have a real impact. After two years as a voyeur to ISIS propaganda and several active war zones, one feels a weight, a dense little cube of sadness, that never really goes away.

Interestingly, as real violence grows more and more accessible, “fake” violence is poised to take another revolutionary step via consumer-grade VR (my Oculus should ship in May). Although it might seem a pretty trivial upgrade to strap a high-definition screen to your head instead of using a television, in fact, it totally reshapes how people interact with digital worlds. Chris Kohler of Wired described how a simple tech demo, which sees you seated close to a female student and giving language instruction, left him feeling deeply unsettled:

Things started off fairly benign, with the student appearing and sitting down next to you, reading from a textbook. You could choose to teach English to a Japanese student in her bedroom, or Japanese to an American student at a beach house. At one point, and this happens in either scenario, the student leans in very close and asks, “Sensei, how do you read this word?” Then she places the book in front of your face, leaning into you in what can only be described as an extremely intimate manner.

My heart rate went up. The experience triggered the same alarms that would go off if a real-life stranger got so close I could feel her breath.

…

Despite its ability to hijack your senses and immerse you in hyper-realism, the real power of VR may lie in its ability to foster quiet intimacy so realistic it’s unsettling.

Left: An early version of the Oculus Rift. Right: A screenshot of “Summer Lesson,” courtesy of Bandai Namco. What will VR be like when the subject matter is less innocent?

Although there has been some discussion of virtual reality’s ability to echo romantic intimacy (you can bet porn companies are stampeding to explore this new frontier), there has been little thought given so far to VR’s ability to simulate the intimacy of violence. I’d bet, given some of the breathless reviews I’ve read of scenarios like plane crashes and bungee jumping, that the violent games to emerge on this platform will be deeply, deeply disturbing. Yet — to a generation already saturated in photorealistic violence — there will surely be no shortage of players.

There was a famous study conducted at the conclusion of World War II by S.L.A. Marshall, chief U.S. Army historian, that determined only 25 percent of U.S. soldiers had fired their weapons in combat and an even smaller proportion had willfully targeted enemy soldiers. This finding was extrapolated in Dave Grossman’s On Killing to argue that most American soldiers were held by a moral compunction against killing that they simply could not overcome. It was due much in part, Grossman wrote, because the soldiers’ upbringing made the idea of taking a life both alien and morally repugnant. The most vivid violence they had been exposed to as children was likely a few comic book illustrations.

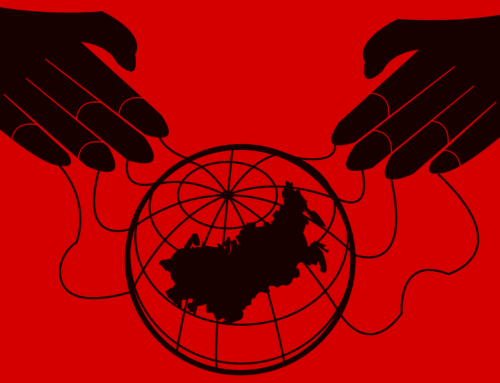

Not so today. Violence seems to be encroaching from both ends. Raw footage of war and death has never been easier to find, while fake simulation of the same has never seemed more real. Ironically, our culture — enlightened and technologically sophisticated — has never stood so close to these darkest reflections of human nature.

Leave A Comment