Ernest Hemingway, “Mussolini, Europe’s Prize Bluffer,” The Toronto Daily Star, January 27, 1923

Note: Dispatch from the 1923 Conference of Lausanne, an international conference updating treaties in wake of the rise of Turkey, notably attended by Benito Mussolini of Italy. The Gabriele D’Annunzio cited was an Italian nationalist of an older breed. His opposition to Mussolini would come of nothing.

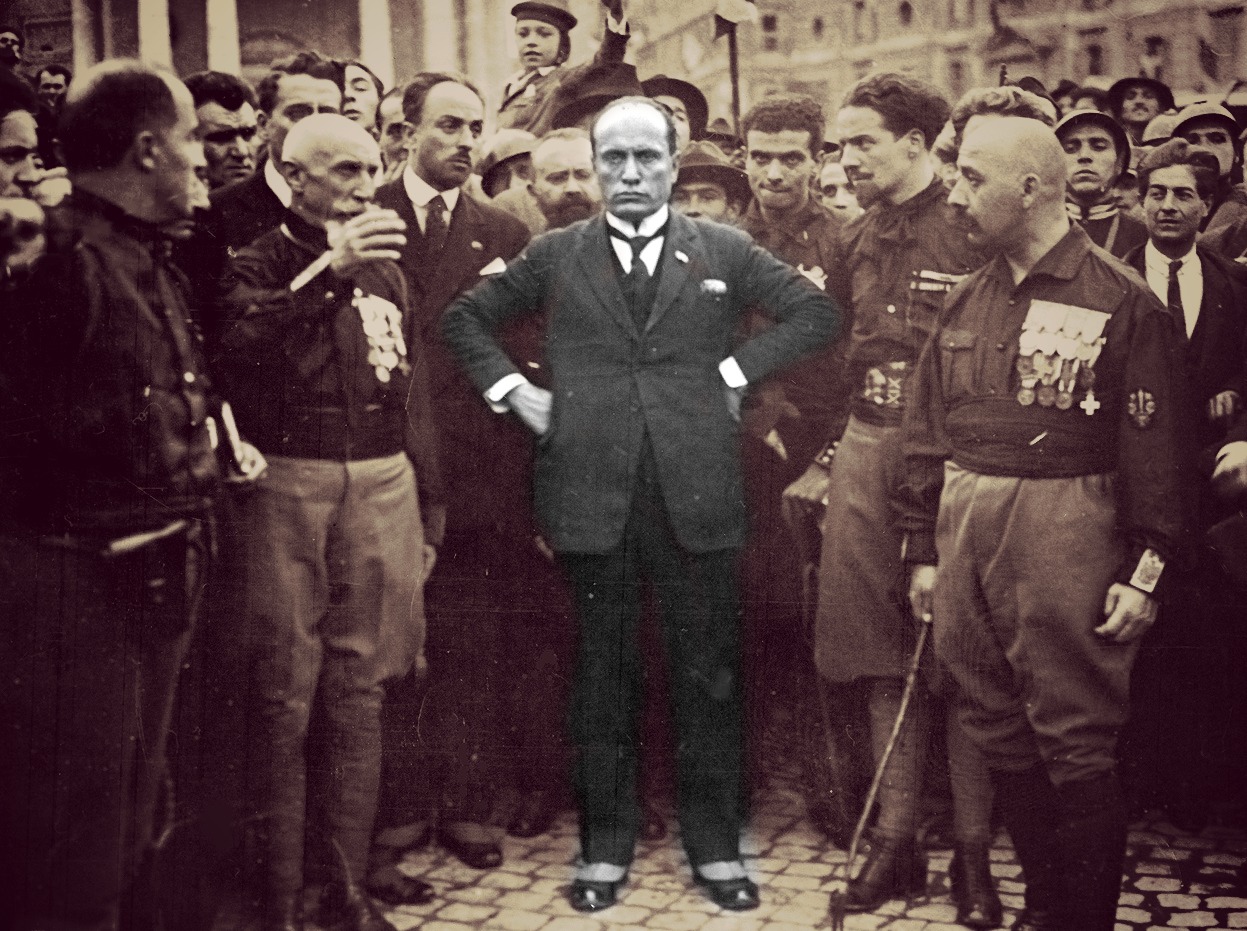

Mussolini is the biggest bluff in Europe. If Mussolini would have me taken out and shot tomorrow morning I would still regard him as a bluff. The shooting would be a bluff. Get hold a good photo of Signor Mussolini sometime and study it. You still see the weakness in his mouth which forces him to scowl the famous Mussolini scowl that is imitated by every 19-year-old Fascisto in Italy. Study his past record. Study the coalition that Fascismo is between capital and labor and consider the history of past coalitions. Study his genius for clothing small ideas in big words. Study his propensity for dueling. Really brave men do not have to fight duels, and many cowards duel constantly to make themselves believe they are brave. And then look at his black shirt and white spats. There is something wrong, even histrionically, with a man who wears white spats with a black shirt.

There is not space here to go into the question of Mussolini as a bluff or as a great and lasting force. Mussolini may last fifteen years or he may be overthrown next spring by Gabriele D’Annunzio, who hates him. But let me give two true pictures of Mussolini at Lausanne.

The Fascist dictator had announced he would receive the press. Everybody came. We all crowded into the room. Mussolini sat at his desk reading a book. His face was contorted into the famous frown. He was registering Dictator. Being an ex-newspaperman himself he knew how many readers would be reached by the accounts the men in the room would write of the interview he was about to give. And he remained absorbed in his book. Mentally he was already reading the lines of the two thousand papers served by the two hundred correspondents. “As we entered the room the Black Shirt Dictator did not look up from the book he was reading, so intense was his concentration, etc.”

I tiptoed over behind him to see what the book was he was reading with such avid interest. It was a French-English dictionary–held upside down.

The other picture of Mussolini as Dictator was on the same day when a group of Italian women living in Lausanne came to the suite of rooms at the Beau Rivage Hotel to present him with a bouquet of roses. There were six women of the peasant class, wives of workmen living in Lausanne, and they stood outside the door waiting to do honor to Italy’s new national hero who was their hero. Mussolini came out of the door in his frock coat, his gray trousers and his white spats. One of the women stepped forward and commenced her speech. Mussolini scowled at her, sneered, let his big-whited African eyes roll over the other five women and went back into the room. The unattractive peasant women in their Sunday clothes were left holding their roses. Mussolini had registered Dictator.

Half an hour later he met Clare Sheridan, who has smiled her way into many interviews, and had time for half an hour’s talk with her.

Of course the newspaper correspondents of Napoleon’s time may have seen the same things in Napoleon, and the men who worked on the Giornale d’Italia in Caesar’s day may have found the same discrepancies in Julius, but after an intimate study of the subject there seems to be a good deal more of Bottomley, an enormous, warlike, duel-fighting, successful Italian Horatio Bottomley, in Mussolini than there does of Napoleon.

It isn’t really Bottomley though. Bottomley was a great fool. Mussolini isn’t a fool and he is a great organizer. But it is a very dangerous thing to organize the patriotism of a nation if you are not sincere, especially when you work its patriotism to such a pitch that it offers to loan money to the government without interest. Once the Latin has sunk his money in a business he wants results and he is going to show Signor Mussolini that it is much easier to be the opposition to a government than to run the government yourself.

A new opposition will rise, it is forming already, and it will be led by that bold, bald-headed, perhaps a little insane but thoroughly sincere, divinely brave swashbuckler, Gabriele D’Annunzio.

[…] Someone who understood that overwhelming passion is the fuel that makes the creative soul run. A “bold, bald-headed, perhaps a little insane but thoroughly sincere, divinely brave swashbuckler” — as a young sometime-fan named Ernest Hemingway once put […]