On the second floor of the King Center in Atlanta, Georgia, among the stately brown suits that Martin Luther King Jr. once wore, there is a dog-eared book. The text is Mahatma Gandhi’s The Story of My Experiments With Truth. You can see King’s scrupulous notes in the margins. If you try hard enough, you can see King himself, deep in thought with a pencil in his hand, laying the intellectual foundation of the movement that he would lead.

Then try following King’s footsteps to India. To the Raj Gat in Delhi, where Gandhi was cremated and where King once laid a wreath before the eternally burning flame. To the Sabarmati Ashram in the city of Ahmedabad, where a diminutive Indian barrister cast off his Western clothes and fancy tastes and found the asceticism that he would keep until his death. You can stand in the small chamber where King also stood and where Gandhi once slept. And if you try hard enough, you can see Gandhi still, lying awake in the dark, his mind weaving the mythos that would come to be associated with freedom for 300 million people.

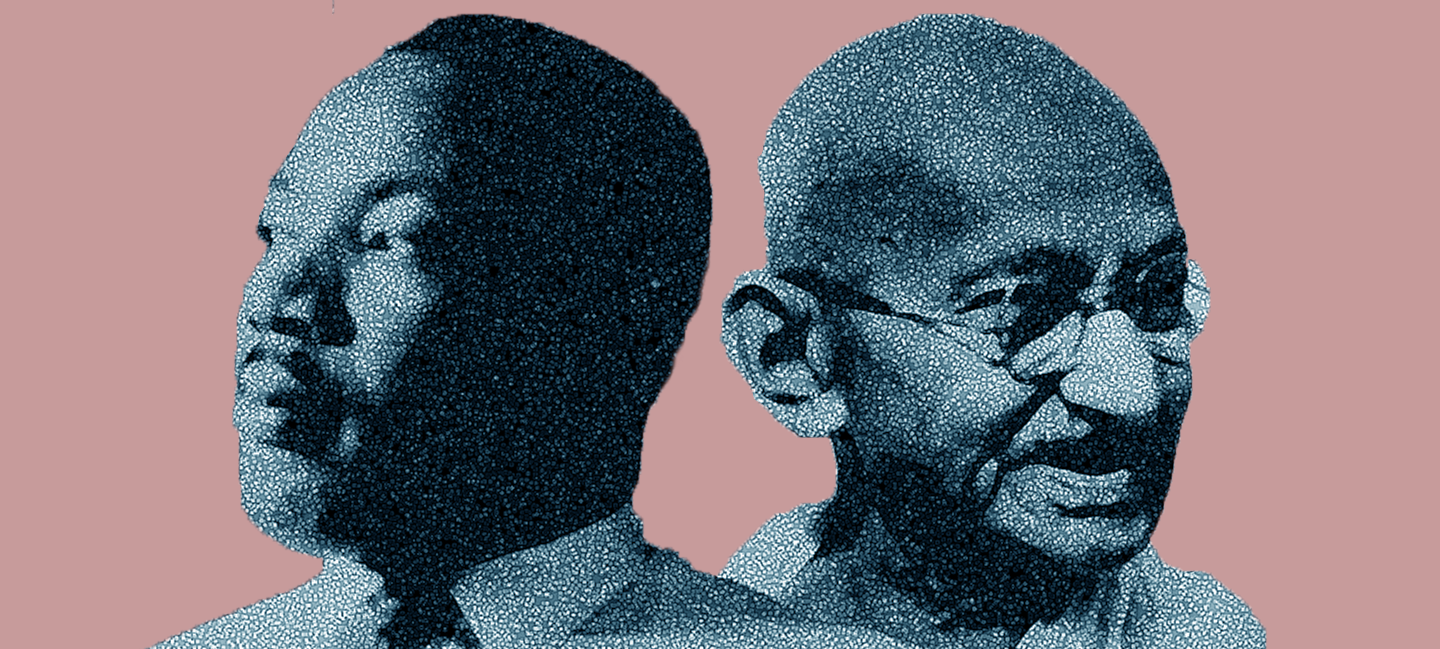

These men are remembered as extraordinary ideological architects. They are remembered as architects, in large part, because they are frozen in amber. They were killed before they could inhabit the things they built.

I wonder how the reputation of King, who had shifted to a broadly anti-war and anti-capitalist platform in the final years of his life, would have fared under Carter Democrats. I also wonder what Gandhi, whose philosophy was so fundamentally at odds with Partition, could have done to soften the cruel realities of post-independence politics. Even now, there are strong revisionist efforts to erode Gandhi’s legacy—and to redeem that of his assassin.

Indeed, historical amnesia has done quite a lot to sand the rough edges off figures like King and Gandhi. The purpose is to make them as inoffensive and politically palatable as possible. Not until my 2017 visit to the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute was I able to engage with King’s bold, strategic, and (for white liberals) often discomfiting activism. I came to realize that the images of King at the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, while extraordinarily powerful, were not most representative of his works. King did not rise to prominence by addressing adoring crowds. He did so by exposing himself to terrifying hostility and frequent imprisonment, using his own vulnerability as a weapon, rarely sure if he would survive the night.

Until my recent visit to Sabarmati Ashram, I knew even less of Gandhi. Western stereotypes have turned him into a vague spiritualist who might bob his head approvingly and whisper namaste to a roomful of mid-career professionals doing hot yoga. I did not realize how cunningly strategic his satyagraha philosophy was. How every aspect of his serenely spiritual persona was intended to advance a very specific political project. His simple white dhoti, for instance, may have demonstrated his disassociation with material possessions, but it was also intended to break the monopoly of the British textile industry by inspiring a return to homespun cloth.

Through their bravery, vision, and martyrdom, the memory of these architects will survive as long as the societies that honor them. But while most schoolchildren know what they did, not enough of us know who they were.

Leave A Comment