I have always wondered what it felt like in Washington, DC in early 2003, as the U.S. military gathered like a storm on the Iraq-Kuwaiti border and the pro-war drum beat reached a fever pitch. I have also wondered how so many smart people were sold on a campaign plan that literally lacked a conclusion.

Unfortunately, I suspect the opinion polls in 2003 looked much as they do now. It is impossible to follow foreign affairs in the nation’s capital and not begin to hear the same distant rhythm: a drumming of op eds and “informed” analyses that suggest a swift Syrian campaign with five or ten or twenty-thousand U.S. soldiers. “Not that many,” they soothe. “Not that long — over before you know it.”

These 500-word war plans (I will not link to them) often read as if they were written by a Henry Kissinger birthday party impersonator, armed with a map, a paintbrush, and too much Vicodin. There are calls for a “Sykes-Picot II” — proposed divisions of Syria so haphazard that they might as well have been the result of a drinking game. References to “Sunni” and “Shia” (and, invariably, “Second Sunni Awakening”) are sprinkled liberally throughout, as if this is the only divide that matters in all the Arab world. There is typically no thought given to either Syrian political economy or Islamic thought. Remarkably, there is also little interest in understanding the enemy. The Islamic “State” is treated like a cohesive political unit; a Nazi Germany transplanted to the twenty-first century.

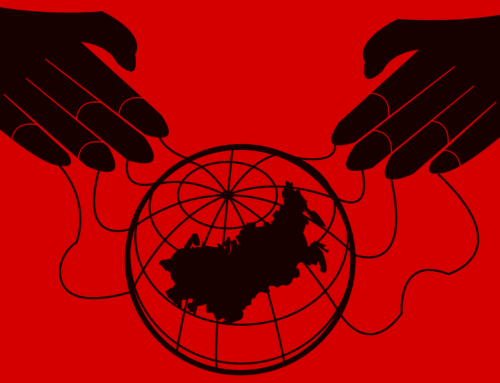

The answer to this black-and-white problem is invariably the application of American power. According to all these pundit-generals, Iraq and Syria have essentially become a Gordion Knot, their disentanglement tried and failed by any number of regional and international actors. This isn’t because the situation is intractable — far from it! Rather, with bold leadership (i.e. not Obama) and commitment (i.e. boots on the ground), the U.S. can solve Syria the same way Alexander severed that troublesome knot. Wham, bam, easy. Home in a month.

It’s not true, but it sounds very nice in a newspaper.

Lost in this chatter is the sheer complexity of even very small and localized conflicts. Modern warfare is a process of perpetually managed chaos. While U.S. defense planners might mitigate risk and work toward a stated end goal, even with superior coordination and force of arms, many elements of the war plan rest on a gambler’s chance. When defense pundits make so many loud and confident pronouncements (“arm the Sunnis and they will do this;” “promise them this and they will do that”), it sounds like they’re playing a game of Risk.

Which would be fine, except some are highly regarded experts whose opinions carry cachet with a number of politicians and would-be presidents. It’s all a DC parlor game, a game of “who’s quoting whom,” until suddenly the proposal in whatever piece or testimony becomes a spark that drives the engine of armed intervention into action.

Months or years later, will the armchair generals stand by the predictions they made, even if so-and-so group did not “rise up” nor the enemy “disintegrate” on schedule? Even if the price paid for such mishaps is the lives of American soldiers?

Of course they won’t. Having enjoyed all the exposure and access, these experts will invariably fix on some “failure in execution” that kept their particular vision from being realized — a tragedy, certainly, but also in no way their fault. The writing will shift to a furious post-mortem followed by conspicuous silence about “x” crisis, as they begin craning their necks looking for the next pot to be stirred.

I’m not anti-war or anti-intervention; I cannot possibly follow the stream of news from Iraq and Syria without thinking that something should be done. However, I also believe in the power of objective analysis — in looking before you leap. “Strategy” is not slicing through the knot. Strategy is thinking very carefully about what happens after the knot is cut.

I’m curious. What is your “plan?”