Originally published (in a superior layout) on Medium.

This is a story about rednecks, the Confederate flag, and the time everyone thought my school was going to get shot up. It’s all true and I wish it wasn’t.

Chances are you feel a couple different things when you see this particular flag on display.

Historically, it exists as an artifact of America’s divided past. In the modern day, it stands as a symbol of choice for the nation’s political fringe. Above all else, it’s a reminder that certain groups of people were once beaten, hunted, and dehumanized, all because of the color of their skin. They suffered these wrongs beneath the banner of the Confederate Flag.

Of course, make these points in certain parts of the country (the parts I’m from) and you’re liable to be shouted down. “Heritage, not Hate!” the cries of protest go. There is a strong and enduring counternarrative that the flag is just that — a flag — easily divorced from its racist roots and screed.

This argument is also bullshit. To disentangle it, let’s start from the beginning.

A No-Good History of a No-Good Thing

The angry mass of stars and bars most folks associate with the failed Confederate States of America was not, in fact, the official flag at all. That honor falls to a much more boring design dreamed up by Southern politicians, mirrored off symbols of the American Revolution and used by almost nobody. Instead, the flag began its life as the battle standard of the Army of North Virginia. Since the Confederacy was at war literally the entire length of its existence, this is the flag that stuck.

You probably also don’t know that the flag enjoyed many years of regal retirement, reserved for solemn parades and Confederate veterans’ funerals, before the Klu Klux Klan went and made it their own. It was a Memorial Day fixture, a common banner for Southern fraternities, and even an occasional standard carried to Europe by Southern-bred Doughboys of World War I. While still the emblem of an old and failed racist regime, it wasn’t yet a symbol of modern racial hatred. This was soon to change.

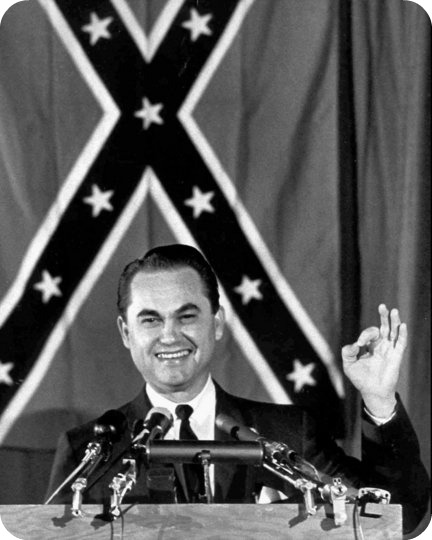

In 1948, when the Democratic Party endorsed a strong civil rights stance, Southern delegates walked out in mass protest, fleeing to Birmingham, Alabama. Once there, they founded the States’ Rights Party, rebranding themselves “Dixiecrats” and selecting a notorious racist as presidential nominee. Their rallying cause was segregation; their rallying banner was the Confederate Flag.

The years that followed should sound familiar to students of American history. As the Civil Rights movement gained momentum through the 1950s and 60s, Southern governors defiantly incorporated the Confederate Flag into their own state banners. They flew the flag in every public place they could, erecting fresh monuments to Confederate war dead even as the tide of public opinion turned against them. Following 1965, as black voters gained real power and schools were at last integrated, the Confederate Flag’s display was increasingly rejected by the courts. Old Dixie slunk further and further from the public eye.

For the Confederate Flag’s dwindling supporters, the most recent decades have been marked by continuous retreat. Only Mississippi still features the flag in its state banner; the other remaining hold-out, Georgia, finally succumbed to national pressure in 2001. The flag is no longer a fixture at Southern football games, nor sanctioned by Southern fraternities. Although the flag still occasionally shows its ugly face at official functions, it is typically the subject of ample attention — and scorn — when it does so.

But is the flag really gone?

The answer to this question is no, no, no. And that’s where my story starts.

***

In sleepy Southern communities far removed from the public eye, this flag remains as common as the Stars and Stripes. To display it is to show pride.

To challenge it is to invite retaliation.

***

The Tale of “Anti-Dixie”

In our high school, that damn flag was everywhere.

It waved at tailgates and football games. It was ubiquitous on license plates and adorned every ball-cap. Thanks to Dixie Outfitters, a t-shirt company that celebrates “Southern Heritage” with images of the Confederate Flag superimposed over gaudy portrayals of deer hunting or bass fishing, it also had a presence in every classroom and school function. The net effect was suffocating. You couldn’t escape it, and if you disagreed with the values it represented — institutionalized racism, sanctioned bigotry — you quickly learned to keep your mouth shut.

One day, a few of us decided we‘d had enough. We were social misfits, tired of a world where all things good were white, evangelical, and Southern. We knew that, in other parts of the country, the Confederate Flag was not displayed so freely and proudly. We decided to bring that same criticism to our own rural Southern hometown, hoping to ban the flag’s display from school grounds. We called ourselves “Anti-Dixie,” started a website, and very shortly ignited a shit storm.

***

Suddenly, the dozens of rednecks who hung out behind the trailers each morning to sneak cigarettes had someone to put in the crosshairs. That morning, they gave him a messed up arm and a black eye. His girlfriend got a similar treatment after school.

The administrators moved quickly. Dixie Outfitters shirts weren’t banned, but Anti-Dixie sure was. They confiscated the offending article and essentially prohibited mention of “Anti-Dixie” altogether. Within hours, it was the talk of a 1,400-person student body. The atmosphere was already boiling hot, but it would soon reach fever pitch.

Other names were leaked. Two more girls got beaten up on the bus. Members of the redneck crowd hung around after school and followed us through the parking lot. It wasn’t uncommon to be asked point-blank, with narrowed eyes and a menacing tone, “Which side are you on?”

Soon enough, rumors began swirling about a planned shooting. People told us that a Proud Southerner had figured out the whole Anti-Dixie membership and wanted revenge. We fled the site in a hurry.

At this point, word had spread well beyond school grounds. That next day, eleven armed deputies patrolled the halls. There were random bag inspections, locker searches, and a hunt for weapons that ranged across all the student parking lots. The sense of fear that day was absolutely, unmistakably, terrifyingly real.

As more and more teens called home, the panic grew. By lunchtime, hundreds of students had left for the day. Every few minutes, an announcement would sound, informing yet another student that their parent was here to pick them up. It was an unreal sort of panic that spread to our teachers as they jittered through the day’s lessons, casting frequent glances at the intercom. Many teachers jettisoned their lesson plans entirely, throwing on whatever VHS they had on hand. None of us paid attention, of course — particularly those of us with something to hide.

Anti-Dixie had struck a deep nerve, and we were being made to pay for it accordingly. It was a strange feeling, to know a simple site directed against a patterned flag had stirred up so much raw hate. Overnight, Anti-Dixie had transformed us into outsiders, firmly aligned against the values our community held to be scripture. It hardly mattered if this was the place we’d grown up, too.

The sense of fear was absolutely, unmistakably, terrifyingly real.

Like most fever pitches, this one eventually died down. There never was a shooting, nor was Dixie Outfitters ever banned from campus. The only formal record of that incident is a short blurb, published in the local paper at the end of October, about deputies visiting the school on account of “rumors.” Likewise, the only administrative change was a decision to permanently station a police officer on school grounds.

For nearly a decade, this story sat in the back of my mind, a weird artifact from a generally forgettable high school career. It wasn’t until this past summer, as I hung out with many of Anti-Dixie’s old founding members, that someone happened to bring it up. “Looking back, that whole thing was kind of fucked up, wasn’t it?” he asked.

And as I thought back on it, I realized: it was. And still is.

***

Today, the flag’s vocal supporters still insist it’s “Heritage, not Hate.” They wave it on the steps of state capitols and hoist it over major highways.

Racist, dumb, or just out of touch?

***

Driving Old Dixie Down

I wish I could say, following my experience with Anti-Dixie, that I became an ardent opponent of the Confederate Flag in all its forms. The truth is more complicated.

After high school, I attended a Northern university where the flag was regarded by many folks as darkly as the banner of the 3rd Reich. It was a stark, often unsettling contrast.

In an attempt to bridge these two worlds, I brought a small Confederate Flag with me and hung it alongside the Stars and Stripes. I was convinced that, while the flag had been polluted by racial division and misappropriated by redneck idiots, it could also represent another, deeper heritage: the noblesse oblige of the antebellum South; the brilliance of Southern generalship; the tragic romanticism of the Lost Cause. I studied it, debated it, and even wrote a controversial op-ed about it.

Then, one day, two friends visited my dorm. They were black — a fact that I hadn’t given thought until they glanced at my wall and saw the Stars and Bars glaring angrily back at them. Nothing was said about it and nothing needed to be. In that moment, all my clever, intellectually acrobatic arguments in favor of the flag drained away. This was a symbol under which people I knew and cared about had suffered — a symbol that to this day was waved by racist activists who wanted them dead and gone.

I took down the flag shortly thereafter.

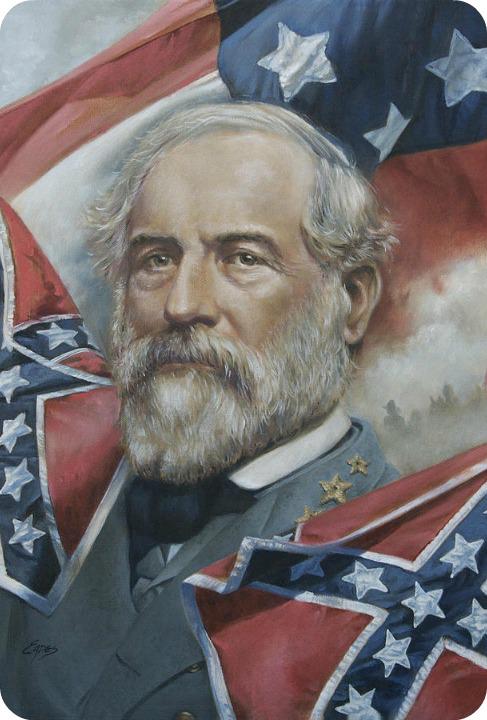

Robert E. Lee: Brilliant tactician, talented general, but no romantic hero. Painting by Linda Blackburn.

The Confederate Flag may well represent Southern heritage, but that particular heritage is firmly grounded in racial hate. The Camelot-like romance of the Antebellum South was built on the back of a slave economy. The strategic triumphs of Robert E. Leeand Stonewall Jacksonwere won, explicitly, in support of a government that sought to keep black Americans in shackles. For the past century, the flag has been used almost exclusively as a banner of white supremacy — and a reminder to black Americans that they still don’t belong.

Of course, this hasn’t kept people from arguing otherwise. Kids still fly itwithout giving much thought to what it means. A 225 square foot Confederate Flag now flaps over I-95, the main artery between Richmond, VA and Washington, DC. A group called the “Virginia Flaggers” travel the state, merrily waving the flag on public grounds. A firefighter leaves his Confederate Flag-painted axe while responding to a house-fire at a black man’s house.

Elsewhere, Kanye West tries to re-appropriate the Confederate Flag and fails. Another (white) artist follows suit and fails harder.

In many cases, it’s insensitivity — not seething racial hatred — that fuels these public incidents. The flag’s vocal supporters may give lip service to the idea of memorializing Confederate war dead, but one suspects that they also enjoy the attention. They see themselves as social provocateurs, attracting scorn and serving an important public function in the process.

They’re also wrong, just as I was.

The Confederate Flag might mean many things to many people, but the heart is rotten. There are still parts of the country where the flag is displayed proudly, without controversy or irony, the same parts where nonwhite faces are often regarded with suspicion bordering on hostility. The same parts where a few rowdy 14-year-olds who dared speak out against it had to receive an armed escort for their trouble.

In the end, the Confederate flag remains the angry mass of nerve endings that bind the three pillars of Southern identity. It’s pride, racism, and loser’s remorse, all in one. It’s a symbol so wrapped up with meaning you couldn’t untangle it if you tried, embraced by people who will never in their lives understand the full sum of what it now represents.

That’s why the flag is still flying on the next generation’s porches and pick-up trucks. That’s why a bunch of teenagers showed such naked wrath when we once upon a time challenged the 142-year-old battle standard of a failed state.

***

In the year 2014, the Confederate Flag belongs in a museum.

Nowhere else.

***

Header courtesy of the talented Gary Arntzen.

I can recall when the whole anti-dixie debacle was going down, but I can’t say I miss Habersham country too much these days. It was a good post.